Anna's Escapes

The following is excerpted from The Cost of Freedom: A Family Memoir of Taiwanese Independence.

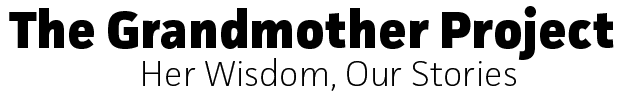

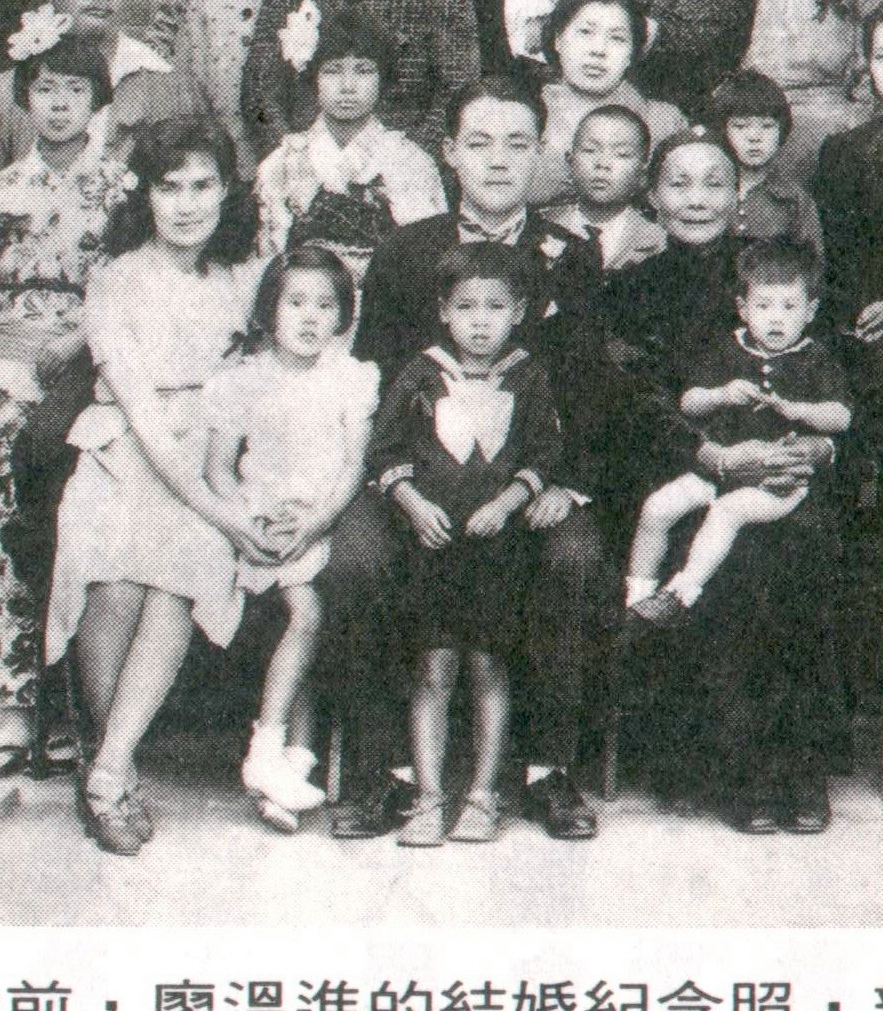

There’s a photograph of my grandmother Anna from when she was twelve years old. As a child, I used to study it, hoping to see myself in her. In the black and white photograph, she wears a satin tunic with a Chinese-style collar, piped with embroidery. It has a burnished shine, and accentuates the Asian features in Anna’s oval face. She sits, looking out into the distance, lips pursed into almost a smile. A large silk bow is perched on her head—in keeping with the style of Chinese girls in the 1920s. When I was very young, I would look at that picture of my grandmother, seeing my own half-Chinese background in her facial features and think, “That’s what I want to look like when I turn twelve.”

By her own accounts, the story of Anna’s life began at age twelve, when she came to live with Miss Banta. My grandmother kept a tight-lipped silence about the years before that—tighter than any of the other silences she had over the years. No regrets, or resentment, or sarcastic asides. Just total silence.

I asked my Aunt Jeanne, the oldest, if she knew more about Grandma Anna’s childhood than my father did. But she only confirmed the absolute lack of information, saying, “Nothing is known about Grandma’s childhood. She never said.”

“Did you ever ask?” I pressed her. “Or did you just know not to?”

“We knew not to. Grandma was private about these things. She got very aggravated if you asked about anything before Miss Banta.”

“Did you ever guess what Grandma’s life was like before she was twelve?” I persisted.

“I have a feeling she was probably abused,” Aunt Jeanne said. She spoke without hesitation, as if she had held this conviction for a long time. “I don’t think Grandma was ever in an orphanage,” she continued. “I think most of the girls who lived with Miss Banta were abused.”

We were both silenced by that possibility.

After that conversation, I tried to imagine what it would be like to keep such a silence, to bury twelve years deep inside myself, as she did. I wondered how she did it. It would be so lonely, I think, keeping such a secret about your own life. My grandmother Anna kept many silences to protect her children—she didn’t tell them much about being an American among the Japanese during World War II, or the danger they faced in Taiwan before she brought them to America, or the sacrifices she made over the years. In these cases, Grandma’s silence was a generous gift: the ignorance of my father and his siblings kept them from experiencing the fear and pain she must have felt. The silence she kept about her own childhood, however, must have been for herself: it was protection from her own memories.

"The silence she kept about her own childhood, however, must have been for herself: it was protection from her own memories."

The year before I left for Taiwan, I went looking for Anna’s birth certificate in New York City’s historical records. I thought, sure, Anna never told her children about what happened. But maybe there were documents out there that could show us what happened, like her birth certificate or adoption records in the department of city records or the genealogical division of the New York Public Library.

Why did Anna’s birth certificate, or her and Thomas’ marriage certificate, even matter to me? It was just such a murky, uncertain thing, Anna’s past. I wanted to prove once and for all, that my grandmother Anna had been born, and had a life before meeting my grandfather, Thomas, and moving to Taiwan with him. Even if this didn’t answer all of my questions, a birth certificate would give me one solid, unquestionable point. A starting point on a map. But no. Nothing. I realized that I didn’t even know the correct birth year: March 19, 1908, or March 19, 1909? No one knew for sure.

Finally, I got access to one of the newspaper databases that had a full text search available from 1865 on, a gift in these early days of digitized news archives. Since Miss Banta was a public figure for working for social justice and welfare, I searched for “Mary Banta” and “True Light Lutheran Church” (which she helped to establish) in the old newspaper archives, and printed every article that came up. As I printed, I studied the headlines:

- “Mary Elizabeth Banta is Dead; Long a Missionary in Chinatown” (an obituary from 1971)

- “Chinatown’s Beloved Teacher Lady Finishes Fifty Years of Emancipating Service” (profile from her retirement and celebratory honors, 1954)

- “Honored by Lutherans: Long Leader and Missionary in Chinatown Cited By Society”

Then, I found a series of sensational stories all centered around a trial in which Miss Banta advocated on behalf of mistreated Chinese children:

- “Say They Are Slaves: Chinese Girls in Court” (New York Tribune, 1909)

- “Chinese Girls Gone: Parents Suggest that Missionaries Enticed Them. Runaways Sought By Police.” (Washington Post 1909)

- “Denies Slave Story” (New York Tribune 1909)

- “Chinese Girl Sent to Home: Father Agrees to Committal—other ‘slave’ case is again adjourned” (New York Tribune 1909)

- “Moy You Toy Sent to a Home” (1909)

These articles, when read all together, detailed an alarming phenomenon in Chinatown in the early 1900s: ‘parents’ or guardians of Chinese girls selling children into foster homes and subjecting them to other forms of abuse. Miss Banta’s work saving children—literally wrenching them out of the grips of exploitation and abuse—was there, in front of me, in well-documented newspaper articles.

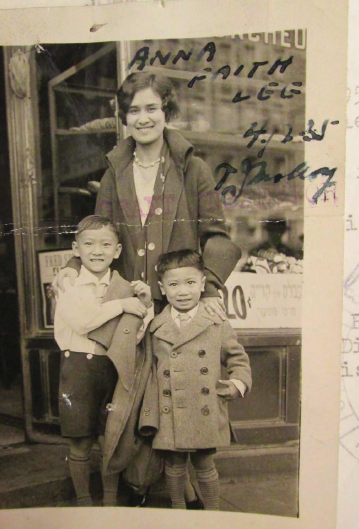

Then I looked at the next page in the stack of printouts. “Annul Marriage of Girl, 12: Youthful Chinese Bride Freed From Ties She Was Forced Into.” The New York Times, Nov. 13, 1920. Nearly 11 or 12 years after Anna’s birth. The article stated:

"Why did Anna’s birth certificate, or her and Thomas’ marriage certificate, even matter to me? It was just such a murky, uncertain thing, Anna’s past. I wanted to prove once and for all, that my grandmother Anna had been born, and had a life before meeting my grandfather."

Anna was either 11 or 12 in 1920. Her official maiden name, which I would later learn from a Social Security Number application filed in the 1950s, was Anna Faith Lee—Faith given to her as a middle name by Miss Banta. Could Lee have been the Kee in this article? Apparently, the Romanized English spelling of Chinese names was very easily confused at this time by everyone, not just the press. Could Kee and Lee have been confused in the translation from Cantonese to English? Or could it have been a typo?

Where did Miss Banta find Anna? How did Anna come to live with Miss Banta? Later I would learn that Anna reported on her social security application that she had been orphaned and taken in by the New York Foundling Home. But what if that foster parent had sold her, as these other girls had been sold? In one of the 1909 articles, I learned that “it was a common practice for Chinamen to buy girls in China for $50 or $60, bring them to this country, keep them until they were fourteen or fifteen years old, and then sell them for $800 to $900.”

In the margins of the article about Anna Wong Kee’s annulled marriage, I scrawled in pencil: “Could this be Anna???”

Then I shoved it into a prominent place in my research folder, packed full of articles about Miss Banta and Chinatown history, information I would follow up on later, I thought. How would I even attempt to cross reference such an extraordinary article, without Anna’s full name, birth certificate, birth year, records, stories or recollections, and no clue from anyone in the Liao family?

But this article offered a possibility about Anna’s childhood origins, no matter how faint or unsubstantiated. And the other Chinese American girls who had come to live with Miss Banta had been through similarly harrowing experiences to get there.

There was just something about that article. I kept thinking, Who else could it be? So even if I never found out for sure how Anna’s life began, this annulment in Binghamton was one possibility. How do you fill a void of silence with a single sheet of paper?

Taipei, March 1947

They were banging on the door. Their shouts woke her up.

Anna used to have this dream again and again. It was the Japanese soldiers, it was the scary men in Chinatown when she was a child, it was the orphanage where she never had any privacy—the banging and the shouting had followed her through her life. But usually she woke up, and was alone, and it was quiet. It had just been a dream.

This was no dream. It was Taipei, and the KMT secret police were banging on the door.

“Let us in!” they shouted in Mandarin. “We come for Liao Wen-Yi the traitor!”

Baby Alex, sleeping in her room, woke up with a whimper. Anna leapt out of bed, looking for a light in the darkness, and shushed him back to sleep. “It’s okay, it’s okay, just a dream, go back to sleep,” she murmured to herself as much as to her child.

The pounding on the door continued. “If you don’t open up, we will burst in,” they shouted. “We know Liao Wen-Yi and Liao Wen-Kui are in there!”

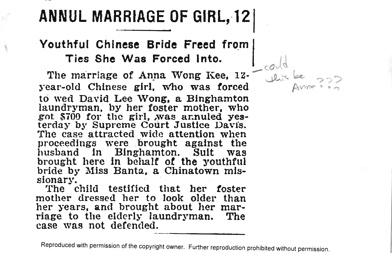

Anna looked frantically around her room. It was the farthest from the front door, and the most secluded. She didn’t want to scare the baby. She pulled on a dressing gown and slippers, and swept her hair off her face as she rushed into the children’s room and gently woke Jeanne and Teddy. They looked up at her sleepily. She forced herself to stay calm. “There are some men here I need to talk to,” she whispered. “Go into my bedroom and keep Baby Alex safe and quiet. Snuggle up in my bed and I’ll be back in a few minutes.” They nodded and slipped into the back bedroom.

Although Jeanne and Teddy could be rowdy, they knew very well now that when adults were talking about “serious things,” it was best to leave the room. Many of Thomas and Joshua’s political meetings at the apartment had grown heated, but Anna explained to the children that they should just play in another room, and not tell anyone else about those “serious adult talks.”

The pounding on the door continued. “Let us in!” they shouted. “You can’t hide. We know you are in there. You can’t hide from justice.”

Anna angrily threw open the door and stood there, eyes flashing, blocking the doorway. “Liao Wen-Yi is not here!” she hissed. “And you have woken up my children. He is not here. You should look somewhere else.”

Unlike the Japanese soldiers from two years earlier, the KMT secret police officer who stood in front of her raised his rifle and aimed it at her face, point blank, inches away. “Stand back, Mrs. Liao,” he said. “We will be the judge of whether Liao Wen-Yi is here or not.”

With her muscles tensed so tightly she felt ready to burst, Anna took two small steps back, out of the doorway, and let the two police agents enter. You will be no good to anyone in your family if you are dead, she reminded herself.

The secret police stomped around the ornate apartment, heavy boots clomping, dark helmets rattling loosely on their heads. They wore full body armor, which was splotched red-brown by layers of dried blood from the previous day’s arrests and murders. They tore the beautiful furnishings apart, overturning tables, cutting through the rice paper walls with bayonets, breaking decorative pottery, rifling through piles of papers and newspapers and political writings on Thomas’ desk, which rained down around them in soft white petals.

Anna felt as if this, too, could be a dream. The next morning, she would wake up and roll over and Thomas would be sleeping next to her in his silk pajamas. And she would say, “I had the scariest dream. They were looking for you because of your political critiques, Chiang Kai-Shek’s henchmen, and they destroyed the house.”

And he would put his arms around her and hold her close and say, “Don’t you worry, that was just a dream. I’ll protect you and the kids,” and they would fall back asleep in a peaceful reverie.

Now she watched as all of their treasures were destroyed. She finally stepped between the secret police agents and the master bedroom, saying, “I will show you that my husband is not in here. But if you even touch my children, with God as my witness, I will kill you with my bare hands. I’ll claw out your eyes with my fingernails.”

The men laughed, but then quieted down when they saw her face. Anna slid open the mahogany and rice paper door, which was decorated with Kanji calligraphy. Six pairs of big dark eyes silently blinked up at them from her bed. She brusquely slid the door shut again.

“So you see,” she said. “Liao Wen-Yi is not here. In fact, he is not in Taiwan. He went on a trip before this madness began. I think it is obvious that he will not be coming back.”

The lead secret police agent sneered. “We do not believe you. Surely he will have to come back for his wife and children, you are like bait for catching a fish.” His colleague laughed. “Even if you are telling the truth, we’ll return to check on you. Tell him to present himself as the traitor he is. Next time, if you can’t produce him, we won’t be so polite.”

He suddenly swept his bayonet across her shoulder, ripping her robe open and exposing Anna’s bare shoulder and nightgown strap. She gasped. A thin red ribbon of blood bloomed above her collarbone with a stinging sensation. She pressed her robe against it to stop the bleeding, and the silk was stained red. Anna froze. These men are capable of anything.

Speaking a harsh Beijing dialect to each other, they stomped out, leaving the apartment door wide open. Anna closed and locked the front door, and found a clean towel and soaked it in water before pressing it her shoulder, which had quickly gone numb. She wandered through the ransacked apartment, feeling the enormity of the changes taking place in Taipei. It was no longer safe here. She hadn’t heard from Thomas yet, but assumed that he had heard about the 2/28 riot from his safe perch in Shanghai. She prayed the KMT hadn’t found him and arrested him there. Then she prayed for herself, and for her children. If the police came back the next day, what would she do then? Who could protect them now?

When she finally returned to the bedroom, the kids were all asleep, limbs akimbo across the bed, on top of the covers. She lay between her children that night, stroking their hair but not sleeping, eyes wide open. This was no dream. This was a waking nightmare, and somehow, she had to find a way to escape.

Kim Liao is a writer and Writing Lecturer at John Jay College of Criminal Justice. Her writing has appeared in The New York Times, Catapult, Lit Hub, The Rumpus, Salon, The Millions, River Teeth, Vol. 1 Brooklyn, Fringe, and others. She is currently revising The Cost of Freedom: A Family Memoir of Taiwanese Independence, and hopes to find a great home for it soon.