“Any relic of the dead is precious, if they were valued living.”—Emily Brontë

I am the keeper of the coins now.

Ottoman Empire coins. My grandmother, Lucy Armaganian (the girl in this photo), was an Armenian refugee who fled Smyrna, Turkey (now called Izmir) after the Great Fire in 1922. She landed in New York Harbor at age 14, wearing as many layers of clothes as she possibly could so they wouldn’t be taken away, and with these little Ottoman Empire coins hidden between her toes. I am the keeper of the coins now. They live on a long chain hanging on my bedroom wall.—Keirsten Geise

The silence she kept about her own childhood must have been for herself: it was protection from her own memories.

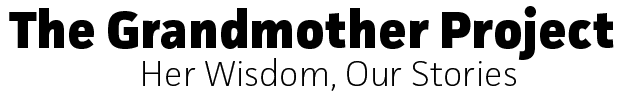

1920 newspaper article. The year before I left for Taiwan, I went looking for my grandmother Anna’s birth certificate in New York City’s historical records. I thought, sure, Anna never told her children about what happened. But maybe there were documents out there that could show us what happened, like her birth certificate or adoption records [before she was taken in by Miss Banta, a missionary].

Finally, I got access to one of the newspaper databases that had a full text search available from 1865 on, a gift in these early days of digitized news archives. Since Miss Banta was a public figure for working for social justice and welfare, I searched for “Mary Banta” and “True Light Lutheran Church” (which she helped to establish) in the old newspaper archives, and printed every article that came up....

These articles, when read all together, detailed an alarming phenomenon in Chinatown in the early 1900s: ‘parents’ or guardians of Chinese girls selling children into foster homes and subjecting them to other forms of abuse. Miss Banta’s work saving children—literally wrenching them out of the grips of exploitation and abuse—was there, in front of me, in well-documented newspaper articles.

Then I looked at the next page in the stack of printouts. “Annul Marriage of Girl, 12: Youthful Chinese Bride Freed From Ties She Was Forced Into.” The New York Times, Nov. 13, 1920.

Anna was either 11 or 12 in 1920. Her official maiden name, which I would later learn from a Social Security Number application filed in the 1950s, was Anna Faith Lee—Faith given to her as a middle name by Miss Banta. Could Lee have been the Kee in this article? Apparently, the Romanized English spelling of Chinese names was very easily confused at this time by everyone, not just the press. Could Kee and Lee have been confused in the translation from Cantonese to English? Or could it have been a typo?

Where did Miss Banta find Anna? How did Anna come to live with Miss Banta? Later I would learn that Anna reported on her social security application that she had been orphaned and taken in by the New York Foundling Home. But what if that foster parent had sold her, as these other girls had been sold? In one of the 1909 articles, I learned that “it was a common practice for Chinamen to buy girls in China for $50 or $60, bring them to this country, keep them until they were fourteen or fifteen years old, and then sell them for $800 to $900.”

In the margins of the article about Anna Wong Kee’s annulled marriage, I scrawled in pencil: “Could this be Anna???”

—Kim Liao, from The Cost of Freedom: A Family Memoir of Taiwanese Independence

It isn’t until I’d say recently that I realized Bob got everything out of my effort.

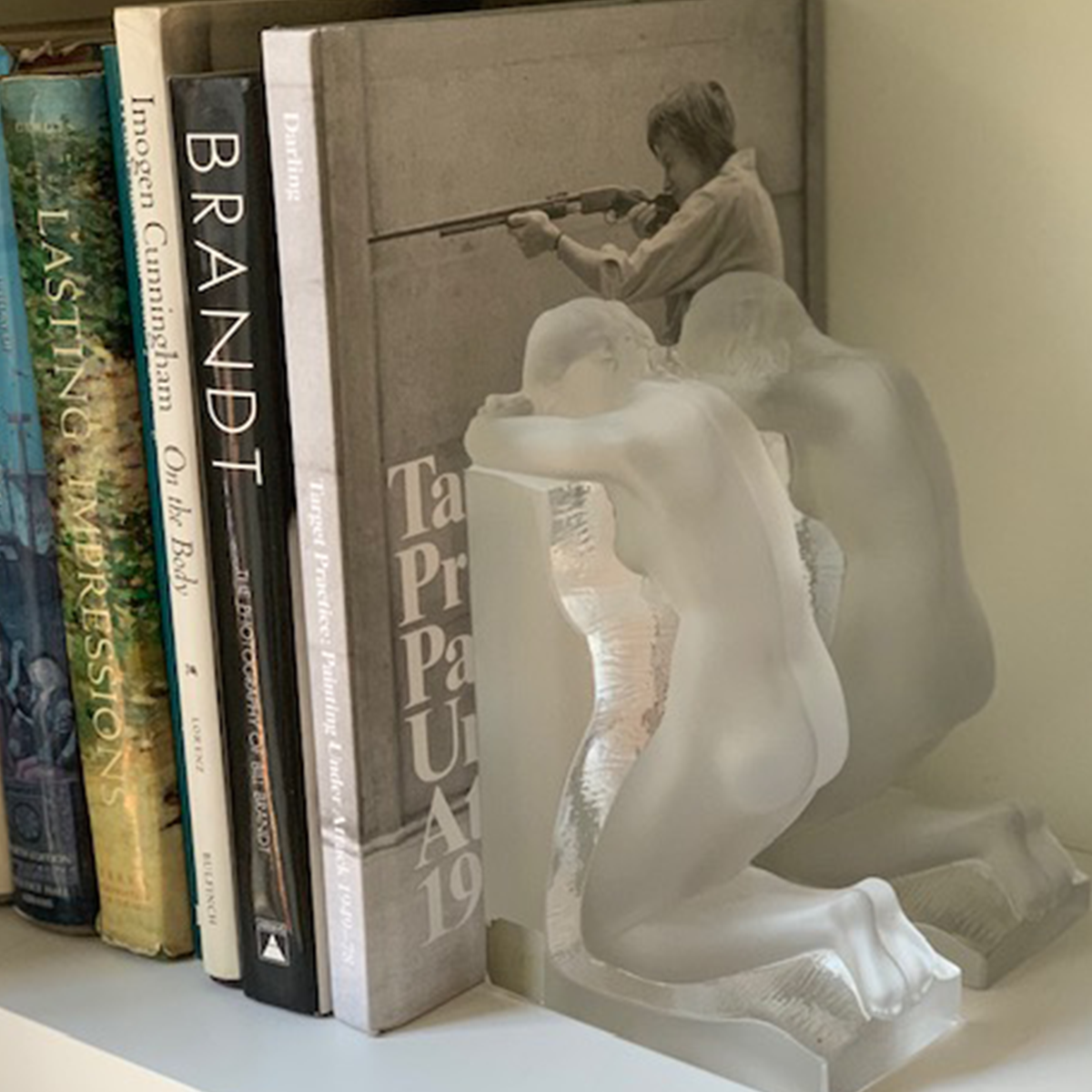

We were almost under Mussolini's nose...

Letter from Florence Carey to her family back home in Ohio. My great aunt travelled from Ohio to New York City and on to Europe in 1936. I have some of her typed letters from that journey: "Chris and I went down and got passes for the stock exchange. Why—If you could see the running and signaling and ticker tape, you’d think you were in a regular nut farm!” Florence and her traveling companions sailed from New York with their Plymouth convertible, aka “Pilly,” over to England, and from there they drove around Europe, ending up in Germany at the Olympics. They also drove through a town where Hitler was stopped, and heard Mussolini speak on the day the sanctions were lifted.—Lauren McFarland

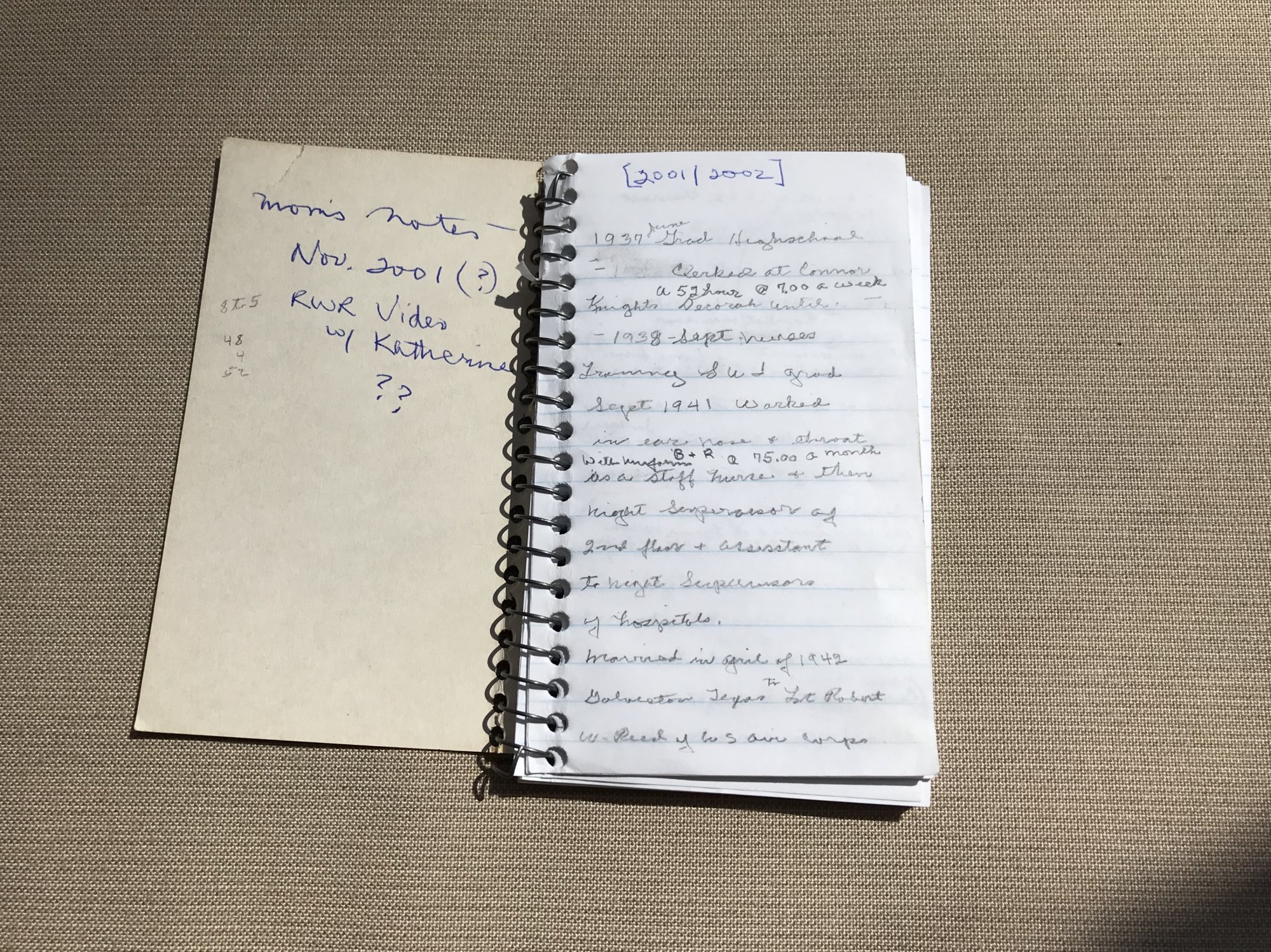

1937-Graduated highschool/Clerked at Connor Knights, 52 hours @ 7.00 dollars a week/until 1938-Sept Nurses training ...

The traces that blessed her with this magic are scattered around her eclectic, Soviet apartment in Tallinn.

Framed prints of women. I believe my grandmother was a magical woman because there exists an absolute absence of bad things about her. This may have been a side effect of my innocent childhood perception, or perhaps it was a magical spell that she cast on her family. I suspect it is the latter, because I remain spellbound to this day.

And I suspect that the traces that blessed her with this magic are scattered around her eclectic, Soviet apartment in Tallinn. The high walls serve as a beige canvas which she adorned with bold framed prints of dignified women. These women evoke an audacity within their viewers, comparable to a tempest of relentless strength. This power showed in her daily, such as when she would be approached by a family member possessed by a snarling demon. In such a case, she would firmly speak magic with caring words and an embrace, and the curse would simply melt away. Such was her compassion, bravery and spirit, and such was her apartment’s decor.—Tiiu Meiner

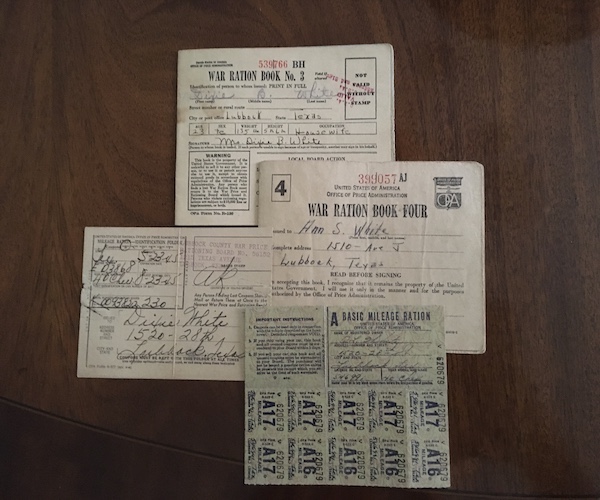

Everyone just accepted the Ration Stamp process and routine as simply something that had to be done.

World War II Ration Stamps. These Ration Stamp Books issued by the War Price and Rationing Board were obtained in Lubbock, Texas. The Stamps covered the purchase of such things as gas, sugar, tires, and shoes. When an item purchased was rationed, the stamp had to be presented. The Stamps couldn’t be traded—they had to come out of your assigned book. If you needed a rationed item, you made sure to have the Book when shopping. Everyone just accepted the Ration Stamp process and routine as simply something that had to be done.—Ann White and her daughter, Judy Hudson

She felt the painting had finally landed where it was meant to be...

1870 lithograph. My grandmother, Dena Thomas, had a grandfather named Ed Slote, who lived in rural southern Michigan. In those days, he would take the train from Chicago to Texas to buy cattle and then would bring those cattle back to Chicago by train. He could ride home for free in the caboose.

On one particular trip in 1870, my great-great-grandfather Ed Slote purchased this painting, “Fast Trotters on Harlem Lane,” at the train station for 50 cents. The painting is a hand-colored lithograph by John Cameron for Currier and Ives. The Harlem Speedway in the picture still exists at 155th Street in Manhattan. In the painting, Commander Cornelius Vanderbilt, the famous railroad magnate, trots past the clubhouse.

This 50-cent picture from 1870 has been passed down in the family ever since. It was with my grandmother Dena Thomas for many years before being passed to her son, Bruce, in Tennessee and then ultimately to me and my family in Canaan, CT last year. My grandmother was so happy to see it hung in our home last Christmas (she passed away earlier this year), and felt it had finally landed where it was meant to be: in a historic farmhouse close to Manhattan.—Ted Michaels