Pulls of Fate

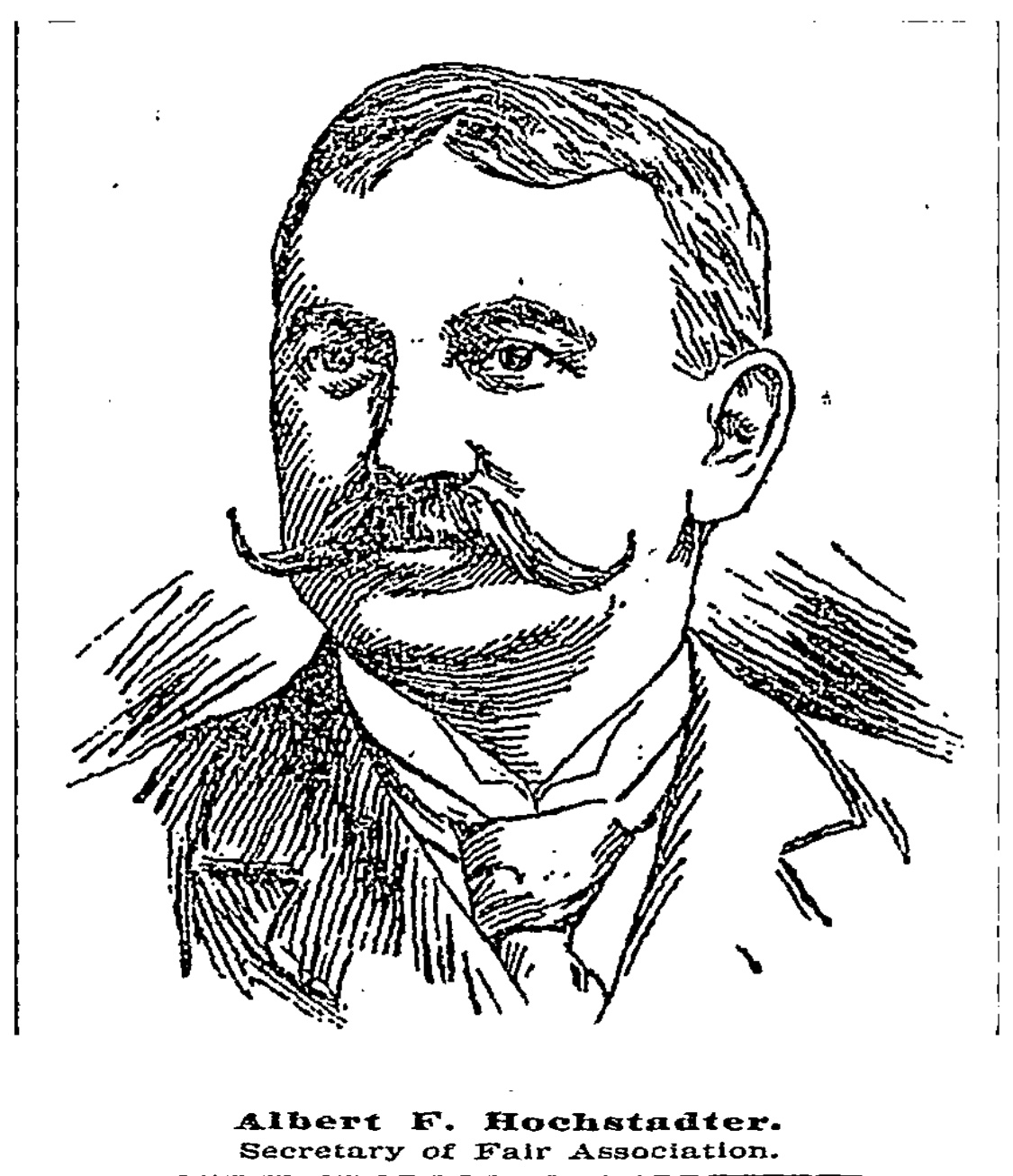

My great-great-grandfather, Albert Hockstader, was, at one point in the late 1890s, the president of the Hebrew Free School Association. I discovered this while reading a New York Times article from December 27, 1898, reporting on a meeting between the HFSA and the Educational Alliance that took place at Temple Emanu-El in New York. At this meeting, the two entities voted on whether to join forces. A few names I knew came to life: Jacob Schiff (Wall Street), Isidor Straus (Macy’s), Theresa Wallach (charitable work), and others were all in the room that day. Mostly, I felt a strange disconnect. Here was a mundane event that happened more than a hundred years ago, and I’m reading about it and realizing, I’m related to these people.

And then I remembered something my great-grandmother said in a recorded interview from 1979, which was about the Educational Alliance and how involved her father had been in it, and that not much had been written on the subject. “Someone should write about that,” she said. I listened to this and jotted down a note. Someone should write about that… Should I?

Growing up in Northern California, I didn’t have much knowledge of the German Jewish side of my family. We were relatively removed from the East Coast, even though my family visited once every few years (my father more frequently). Mainly, this detachment grew out of the fact that after my great-grandmother died, my father’s living relatives were not great in number, and so over time the family stories faded. But they did not disappear completely.

Having lived in New York City for twenty-five years now, only in the last few years did it strike me that I have settled down in my family’s old stomping grounds (although I live in Brooklyn and they were between the Upper East and West Sides of Manhattan). I have no idea why it took me so long to feel that pull of fate I’ve read so much about, to feel it in my own life.

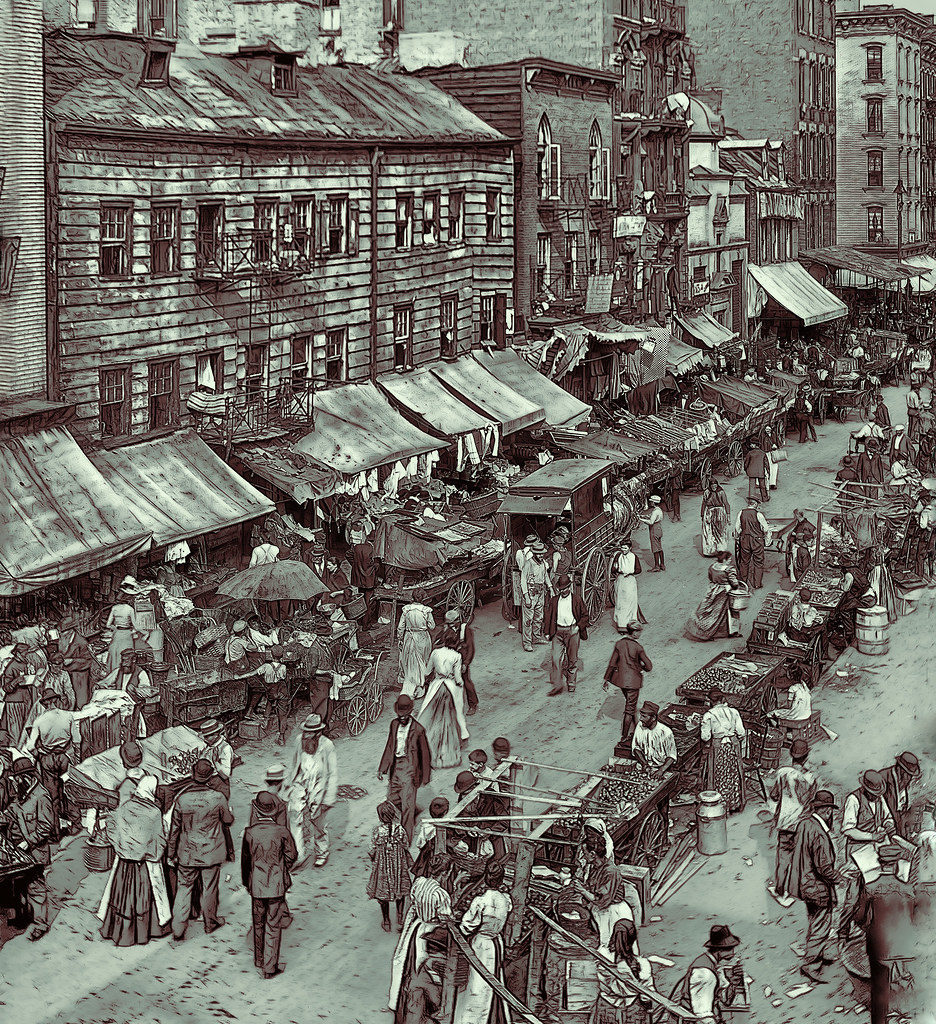

The Hebrew Free School movement started in Philadelphia as early as 1848, but didn’t spread to New York City until 1864, “when Christian missionaries began a concerted effort to seek to convert Jewish immigrant children in New York to Christianity under the guise of offering free Hebrew education,” writes Ariel Kates on Village Preservation. “The Jews of New York pushed back, and that movement was lead by congregations located in Greenwich Village and today’s East Village…. While assimilation into the Public School system of New York was important, Jewish communities were not interested in a kind of assimilation that included conversion. However, many immigrant parents weren’t able to afford private synagogue membership and schools for their children. And so, the Hebrew Free School Association was formed.”

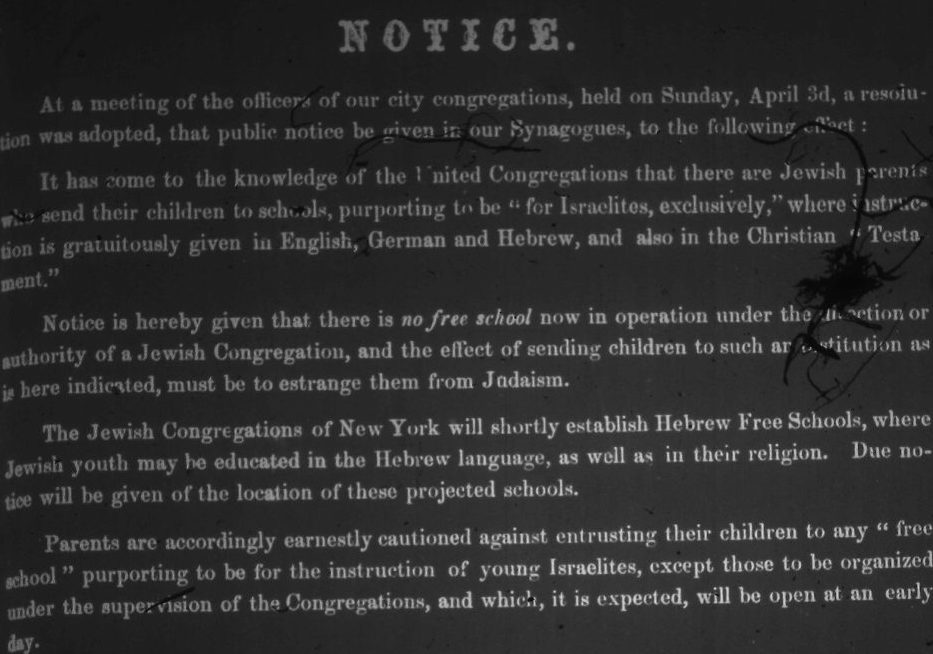

A number of the earliest synagogues in New York came together and drafted a letter to residents, urging them not to join public schools whose aim was to “estrange them from Judaism,” but to join the Hebrew Free Schools newly formed by the Jewish Congregations of New York instead.

NOTICE

At a meeting of the officers of our city congregations, held on Sunday, April 3rd, a resolution was adopted, that public notice be given in our Synagogues, to the following effect:

It has come to the knowledge of the United Congregations that there are Jewish parents who send their children to schools, purporting to be “for Israelites, exclusively,” where instruction is gratuitously given in English, German and Hebrew, and also in the Christian “Testament.”

Notice is hereby given that there is no free school now in operation under the direction or the authority of a Jewish Congregation, and the effect of sending children to such an institution as is here indicated, must be to estrange them from Judaism,

The Jewish Congregations of New York will shortly establish Hebrew Free Schools, where Jewish youth may be educated in the Hebrew language, as well as in their religion. Due notice will be given of the location of these projected schools.

Parents are accordingly earnestly cautioned against entrusting their children to any “free schools” purporting to be for the instruction of young Israelites, except those to be organized under the supervision of the Congregations, and which, it is expected, will be open at an early day.

The reason I’ve been thinking about the Hebrew Free School Association and the Educational Alliance (a.k.a. “The Edgies”) is not only because of my grandmother project. It’s because I recently watched the documentary The U.S. and the Holocaust. For anyone who hasn’t seen it I can only say that, if you are American, you must see it. The United States did close to nothing to help Jewish refugees escape Europe. My own question is: what did the established New York German Jews do to help?

Jacob Schiff (mentioned above) gave large sums to the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (JDC), credited in the film for taking great strides in Europe to save tens of thousands of lives. Schiff’s donations indicate, for me anyway, that others in the crowd would have gathered funds too. Yet as far as I can tell from the documentary and from my own research, the German Jews in New York were restricted by the law of the land at the time: the Immigration Act of 1924, which placed strict quotas on immigration from eastern countries. Even in the face of millions dying, the United States government refused to budge.

The fact of antisemitism in this country is undeniable, but I had no idea how far back it reaches, especially in my new-old home of New York City. Even with the wealth they had cultivated from start-up merchant businesses in the 1850s and 60s, the New York German Jews lived inside unbelievable prejudice and exclusion, from Wall Street lunchrooms, to members-only clubs, to the Astor 400, to hotels and restaurants. Around the time Albert Hockstader was HFSA president, the divisions had reached a peak:

“New York’s Americanized German speaking Jews feared that anti-Semitism and anti-immigrant sentiment would become widespread,” writes EJ Sampson in her paper on the settlement houses of the Lower East Side. “The limits of German Jewish acceptance into top levels of American society were becoming increasingly apparent in the 1890s when they experienced anti-Semitism of a “society” sort in not being accepted into hotels, residences and clubs. Community leaders worried that a large influx of poor traditional Jews with noted radical tendencies would promote anti-Semitism in an era becoming increasingly marked by anti-immigrant eugenics discourses in which Jews were seen as an inferior race.”

There is no excuse for discrimination. On the one hand, the “Americanized” German Jews were a large part of the problem separating the Uptown and Downtown Jewish communities. On the other, groups like the HFSA and the EA were funded by those Uptown with, I have to believe, the good intention of helping the Jewish culture survive Downtown. And if survival in the Gilded Age meant that German Jews had to assimilate, while also bearing the brunt of antisemitism that assimilation created, then I can understand the choices those families (my family) had to make.

As the country headed into the 1930s, however, I really do want to know if they tried to do more. I will keep digging. The Jewish culture was kept alive in New York City in large part because of the HFSA and the Edgies. They voted to merge that long-ago day in December 1898. The Educational Alliance lives on.

Resources: Norfolk Street Archives; Village Preservation; Social Welfare Library; JDC and the JDC Archives; Our Crowd: The Great Jewish Families of New York