Knowing Her Only Through Pictures

I never met my grandmother, whose name was Tillie (Chaya Taube) Green; she died when I was just a few weeks old. There was only one family photo I knew of her during my childhood: it was the formal picture of a serious-looking woman, holding onto her two young daughters: Ida (my mother, the older of the two) and her sister, Yetta. The two daughters held hands with each other, standing on either side of my grandmother. But no one in the picture seems very happy. (Ida and Yetta did not always get along.)

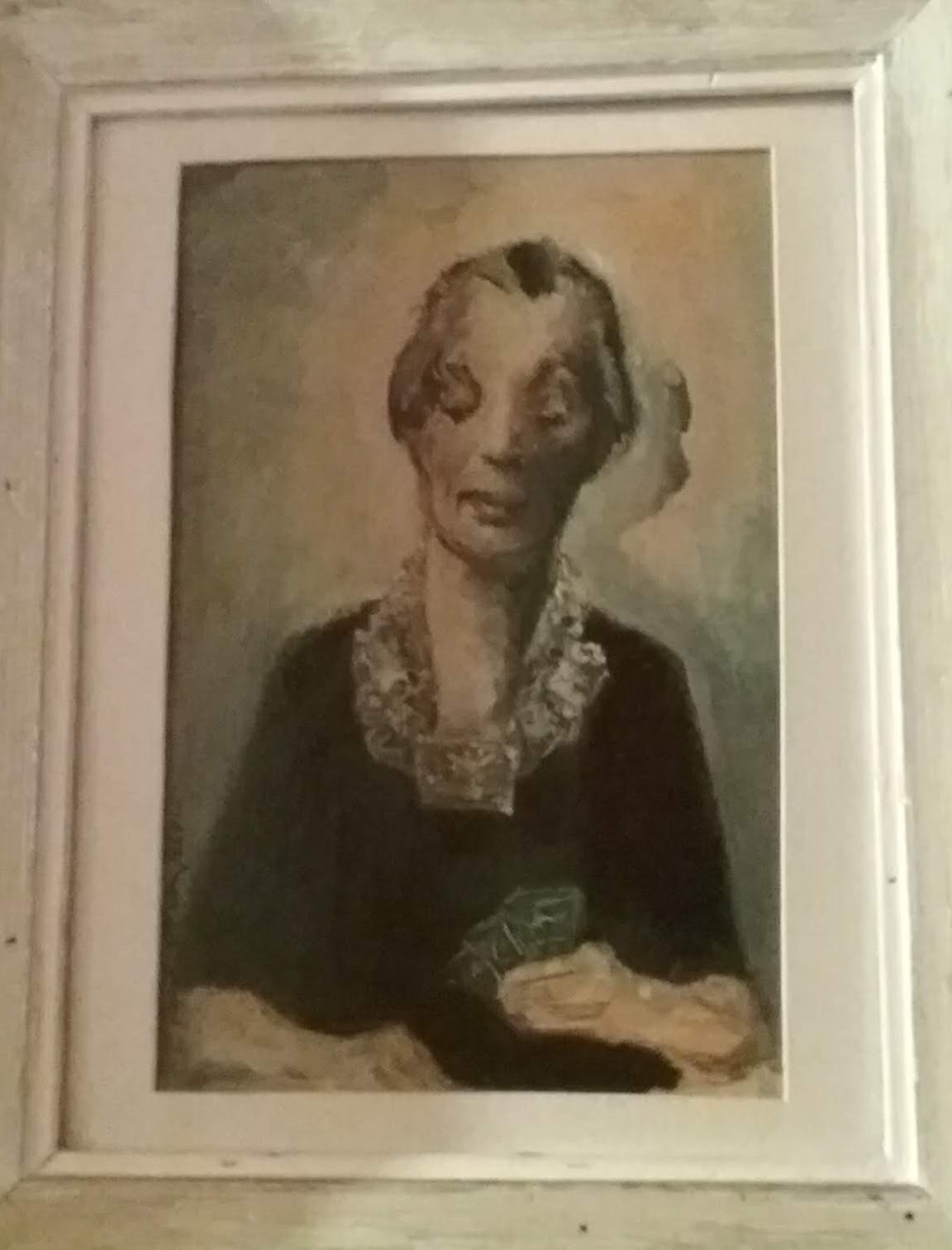

I also remember my grandmother’s portrait, painted by my father, a picture of her playing cards, when she was already near the end of her life. It doesn’t look very much like the woman in the formal photograph. But as my mother aged, she grew to look remarkably like the portrait of her mother that my father had painted many years before.

Tillie Green had a hard life, but apparently not one completely without its rewards.

At the age of 16, in Poland, she was married off to a man she didn’t love, but she ran away and absconded to America. This occurred around the beginning of the 20th century, when America’s doors were open to the hordes of immigrants from Eastern Europe flooding in to fill the many jobs – though poorly paid and in harsh conditions – available in the industrializing nation.

Tillie’s husband followed after her to New York, to find her, and apparently succeeded in locating her. But soon after he arrived, Tillie arranged with a female friend to meet with the husband, on some pretext. When the friend and husband were alone together in his room, lo and behold! – the rabbi and witnesses burst in, to find the husband alone in a room with another woman, not his wife. This was grounds for divorce in Jewish law, and the unwanted spouse was forced to grant my grandmother a get, a Jewish bill of divorce.

Sometime afterwards, Tillie met my grandfather, Jacob Green, a widower with two small boys. Apparently, Tillie cared for the two boys and raised them as her own, and soon also had two girls with Jacob – Ida and Yetta. It was only when I was in my twenties that I learned that my uncles were only half-brothers to my mother.

The family was poor. Jacob was a “kluks-oprator,” a sewing machine operator in the sweat shops of the New York garment industry. He worked long hours, came home exhausted and went to sleep. To augment the family’s income, Tillie also worked as a seamstress, at home, sewing into the night, as my mother recalled.

Still a relatively young man, in his early fifties, Jacob died of an apparently curable disease. But the hospital did not have the necessary medication, and my mother ran around the city trying to locate it, but it was too late.

Thus, Tillie was widowed at the age of approximately 51, and never remarried. She passed away at 65 – a fairly old woman by then.

Beyond these stories, I never learned very much about my grandmother. My mother didn’t talk about her much, but apparently my grandmother had believed that it was harmful to a child’s upbringing to lavish praise on a youngster. As a result, my mother never received the praise she so desperately craved while growing up. She once overheard her mother telling a neighbor that she was very proud of my mother’s academic achievements, but of course would never tell her that. What a sad mistake.

I also learned from my father that my mother inherited my grandmother’s lack of culinary skills.

After my mother’s death in 2007, I was cleaning out the family house and came upon a photo, stuck away deep in a shelf in the basement, of a young and robust woman in a long white dress, with a big smile. I didn’t recognize the face at first, but then later realized that this was undoubtedly a picture taken of my grandmother at her wedding – taken when she was still quite young and fresh-faced.

Busy with the house-cleaning, I only looked at this photo that one time when I found it, and then slipped it into a box of books that I was taking home with me. But then I called a charity-operated thrift shop to come and take away some of the many boxes of books that I didn’t want. The men came in and swooped up the boxes, and by mistake took the box of books containing my grandmother’s wedding picture.

I tried desperately to retrieve the photo, calling the charity to search its warehouse, but the photo was gone. We checked in at the various outlets that the charity managed, and they conducted a search of their own, but to no avail. I had seen that photo of my grandmother as a smiling, happy, pretty, sparkling young woman just that one time and never had the chance to see it again.

David Kronfeld recently retired from a career in corporate communications, and now is working on his own writing projects. He lives in New York City.